Cyprus for Sale:

Power, Corruption and a Golden Visa Scheme

It is a cliche from Bond to Bourne: the classic spy image of a suitcase filled with cash and multiple passports for a quick getaway. But increasingly it is not spies that are looking for a second passport, but a growing number of 'economic citizens' - Kim Gittelson, BBC Reporter. New York

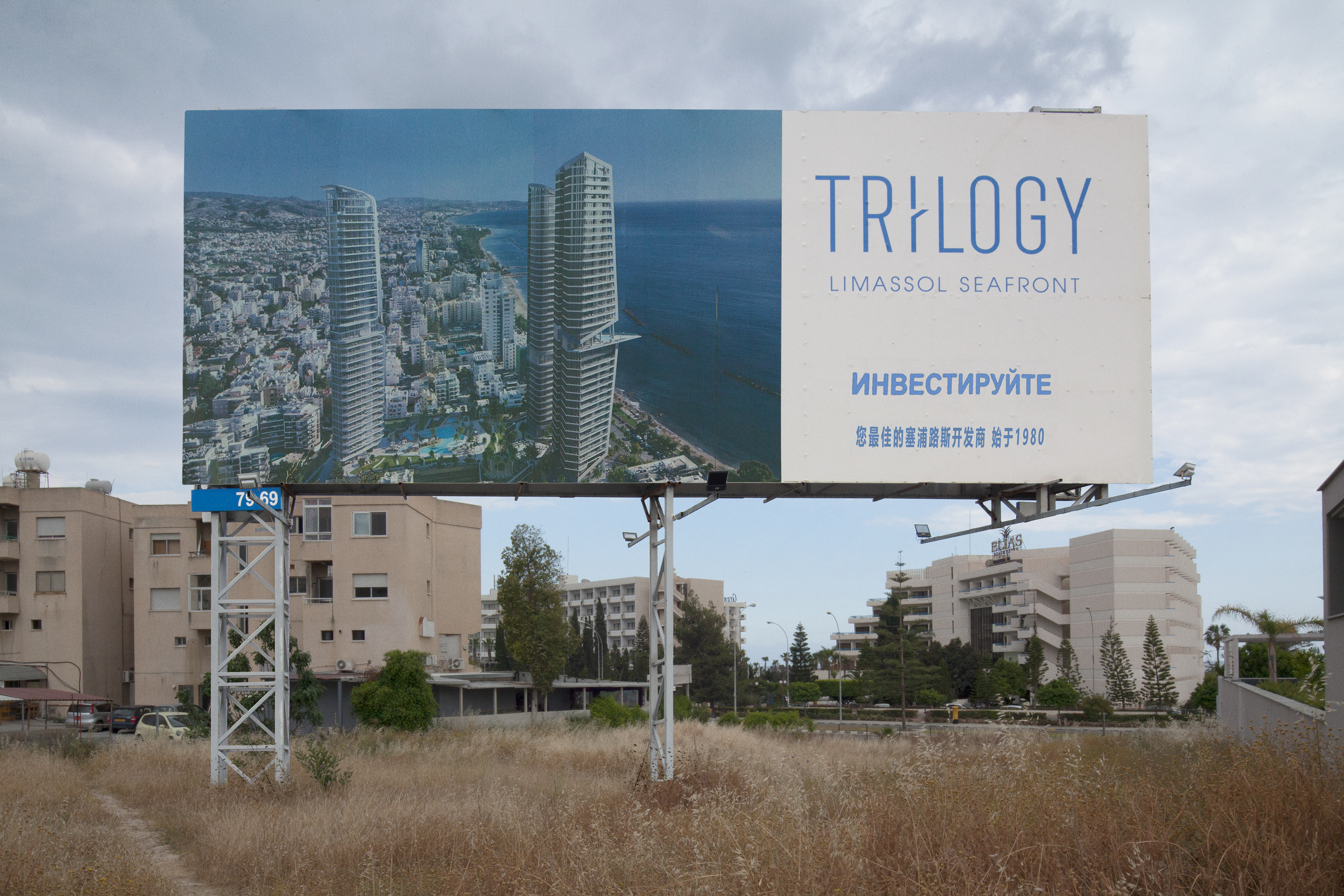

A particular clientele. The buildings being developed in these cities are not even marketed to Cypriots. Billboards market real estate investments in foreign languages, and the sale of visas is marketed aggressively at international airports.

A two-tier system. Countries seeking to attract foreign investment via the scheme have shifted their immigration policies towards a two-tier system, whereby the wealthy have a completely different set of laws and regulations from the ordinary population. The wasteful utilization of resources for the benefit of just a handful of wealthy “investors” results in the everyday people suffering the effects of gentrification and rising prices.

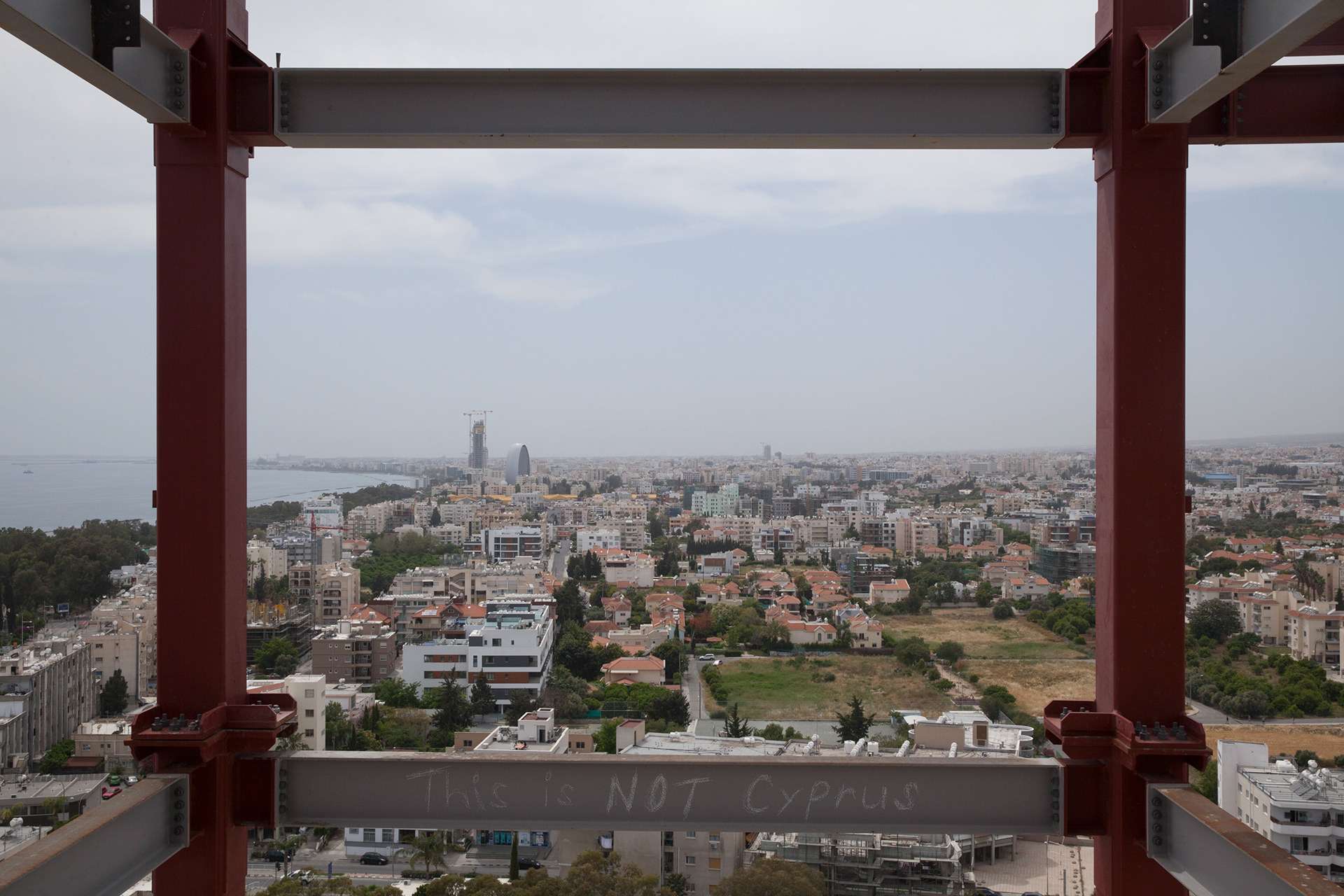

Alien obstruction. Many of the new buildings block the views of old residential areas. Architecturally, they are ruining the visual character of cities such as Limassol. The architecture of such buildings is intrusive, its size and shape reflecting the power and exploitative relations in which they are being brought into the picture, while its luxury kitsch aesthetic speaks a language to which the locals can only find empty in meaning.

Environmental Disregard. The developers have carte blanche on how high they can build and where they want to build without considering how this will impact the environment, the economy and the quality of life of citizens.

Gentrification of the middle-class. Although citizenship and residency rights are acquired, in many cases those who obtain them do not reside in the country, leaving their luxury houses and flats empty. The wasteful utilization of resources for the benefit of just a handful of wealthy “investors” results in the everyday people suffering the effects of gentrification and rising prices.

Identikit. Applicants are usually accepted in the scheme without background checks and, as a result, some of the investors have been found to be well-known international criminals who pay a little extra to acquire citizenship for themselves and their families.

New kid on the block. The Anastasiades government attempted to generate revenues by selling citizenship to wealthy “investors” who bought up apartments in the newly unveiled towers that sprang up like mushrooms, primarily in Limassol and Nicosia.

Occupied but empty. The vast majority of “investors” are phantom individuals who do not contribute to the local economy. In fact, many of them do not even live in Cyprus. Some of them also have shell companies to launder money and own flats that remain empty.

Office for rent. As inequality rises, many middle and lower middle-strata house and flat-owners choose to work from home and are willing to either liquidate their assets by selling or renting their properties to investors themselves.

This is NOT Cyprus. In an attempt to investigate money laundering in English Premier League by billionaire investors, Al Jazeera were directed to Cyprus, as a potential gateway of earning a passport to be allowed to do dealings elsewhere . Following the money seemed to be the right strategy in uncovering a side of Cyprus which has since become a source of shame on the part of many Cypriots, outrage, ridicule and refusal to accept that “this is Cyprus”; as quoted by a corrupt Cypriot lawyer involved in the scandal.

Order of the day. To combat the rising inequality, municipalities have announced plans to construct low-cost housing. It is not clear whether the plans will resolve the housing problem or whether they will accelerate the movement of old residents into parts of the city that are deemed as unmarketable to “investors”. Such housing schemes seem like an exoneration of the visa scheme

Phantom Investors. The vast majority of investors are phantom individuals who do not contribute to the local economy. In fact, many of them do not even live in Cyprus.

The irony of Lady. The only area in Limassol that remains unaffected is the area around Lady’s Mile Beach. The area is adjacent to Akrotiri RAF military base where gigantic British radio-listening communication antennas loom over the landscape. The military base is a vestige of British colonialism that still remains active, often partaking in military operations in the Middle East. s Mile

The trickle down theory. The colonization of city space by new developments was viewed as a minor consequence of “development” at first, but has grown into a major problem for the city of Limassol. The fading middle-strata might still have the illusion of trickle-down profits, but the lower working class have been displaced to the outskirts of the city, unable to find a voice. Rents in Limassol have risen exponentially in recent years, excluding many Cypriots and other residents.

The young couple dilemma. Many young people end up residing with their parents even after they are married. Others live in nearby villages, or, if commuting is not an option, sharing flats. To combat the rising inequality, municipalities such as in Limassol have announced plans to construct low-cost housing. It is not clear, however, whether the plans will resolve the housing problem or whether they will accelerate the movement of old residents into parts of the city that are deemed as unmarketable to “investors”. Such housing schemes seem like an exoneration of the visa scheme.

Turning a blind eye. The alteration of the cultural landscape of Cyprus through the building of luxury apartments well above urban planning red flags, are directly related to the corruption and economic profit made by a small caste of the Cypriot elite

Cyprus for Sale. ‘Cyprus for Sale’ critically explores the phenomenon of the golden visa scheme, which has far-reaching implications for Cypriot society. It ultimately unveils a scandal surrounding the controversial citizenship-for-investment program implemented by the Republic of Cyprus. Although initiated prior to 2013, the scheme rapidly became the primary method for attracting foreign capital to the island, offering Cypriot citizenship and European Union (EU) passports to foreign investors who made substantial financial investments. Most of such investments were directed by a web of actors towards the property market, impacting the Cypriot society along class lines. Environmental concerns, gentrification, and marginalization have transformed cities and affected the daily lives of many citizens. Investigative reports exposed allegations of corruption, money laundering, and lax due diligence within the Golden Visa program. It was revealed that politically connected figures and individuals with questionable backgrounds obtained Cypriot citizenship without proper scrutiny. Despite the government’s portrayal of the scheme as a means of implementing trickle-down economics, these revelations sparked public outrage, demanding reforms and increased transparency.

Rich people are on the move, as John Rennie Short (2010) put it a few years ago. Increasingly, however, this is true not only of the super-rich who flit between global metropolises such as Paris, London and New York. Countries like the Republic of Cyprus are also attracting international “investors” with golden visa schemes that promise visa-free travel and favorable tax regimes. These schemes are designed to legalize and simplify the process of moving concentrated wealth from one country to another, which is especially helpful if it has been made illegally or under dubious circumstances. Countries seeking to attract this flow of wealth have shifted their immigration policies towards a two-tier system, whereby the wealthy have a completely different set of laws and regulations from the ordinary population, those who flee wars or who try to pursue their economic sustenance in a foreign land from that which they were born. Golden visa schemes claim to benefit both countries and investors, arguing that while investors gain residency rights, destination countries gain revenues through investment, which in turn creates employment opportunities for locals.

In practice, however, things are rather different. The housing market experiences a bubble-like phenomenon, people are unable to pay the rising rents, there are increasing concerns about environmental degradation and lack of urban planning… the list goes on. Although citizenship and residency rights are acquired, in many cases those who obtain them do not reside in the country, leaving their luxury houses and flats empty. The wasteful utilization of resources for the benefit of just a handful of wealthy “investors” results in the everyday people suffering the effects of gentrification and rising prices. After multiple media tip toed and hinted towards the issue, the program that existed in Cyprus was eventually uncovered as a mega scandal by a number of independent researchers. The Al Jazeera has, in a rather lucky way, shown the grotesque face of such dealings both as participating individuals and as a systemic process. In an attempt to investigate laundering money in English Premier League by billionaire investors, they were directed to Cyprus, as a potential gateway of earning a passport to be allowed to do dealings elsewhere (such was the process before Brexit). Following the money, it seemed, to be the right strategy in uncovering a side of Cyprus which has since become a source of shame on the part of many Cypriots, outrage, ridicule and refusal to accept that “this is Cyprus”; a rather raw description corrupt lawyer confessed, graphically depicted in the documentary.

NOT THE FIRST TIME

The Republic of Cyprus has attempted to attract wealthy individuals before. Shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the government targeted Russian oligarchs (many of them close to the emerging establishment in the Kremlin), who became rich by looting the former Soviet Union and needed an escape route for their newly found riches. They were attracted by the country’s low flat corporate tax rate, strict privacy laws and the geographic desirability.

Meanwhile, much of the Cypriot political elite were entangled, providing legal services and having close ties to the banks that accepted deposits. As a result, the banking industry boomed in Cyprus, growing to become nine times larger than the country’s economy by 2009. Cypriot banks expanded their operations in Greece, the UK and other external markets in search of further growth and profit, increasing the rate of credit and providing low rates on loans to accommodate the utilization of such over-accumulated capital. This model lasted for about three decades (even if it periodically endured crises, such as the stock exchange bubble of 1999).

In 2013, however, Cyprus experienced a serious financial crisis, in the wake of which the EU proposed a “haircut” on deposits and accounts. The Cypriot center-right government attempted to respond with another, short-sighted and highly controversial scheme. Although the citizenship-by-investment program began in 2002, it moved up the agenda and gained considerable public media attention when Nicos Anastasiades’ government decided to unlock its potential by overcoming “bureaucratic nuances” and announcing “investment motives”, which included allowing the development of high buildings through a special investment framework. Anastasiades’ government attempted to generate revenues by selling citizenship to wealthy “investors” who bought up apartments in the newly unveiled towers that sprang up like mushrooms, primarily in Limassol and most recently to Nicosia. The government lowered the minimum investment required from $11.7 million to $3.5 million in 2013 and again in 2016 to $2.35 million.

Applicants are usually accepted in the scheme without background checks and, as a result, some of the investors have been found to be well-known international criminals who pay a little extra to acquire citizenship for themselves and their families. The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) accused president Anastasiades of having direct and indirect links to the scheme, profiting along with local and foreign elites, some connected to international organized crime. Despite the evidence, however, the president responded that such reports “defame the president and the country”. The Ministry of Finance of the Republic claimed that the scheme was designed to coordinate and simplify the process for investors who establish genuine businesses and in turn legitimately gain permanent residence. In the process, investing in Cyprus became one of the easiest ways to buy an EU passport. In the wake of the Al Jazeera videos and explanations of how it worked, the several loopholes were questioned in the public sphere as being intentionally left there. Then, the president and the Ministry tried to adhere to a narrative of “mistakes” or individuals taking advantage of the program.

NOT FOR LOCALS

The buildings being developed in these cities are not even marketed to Cypriots. Billboards market real estate investments in Russian and Chinese, and the sale of visas is marketed aggressively at international airports. Applicants are usually accepted without background checks. To this end, multiple foreign media have pointed towards the hazy and easily corruptible process. The government has suggested, those who do discuss such matters in the public are potentially harming the brand name of Cyprus, accused of economic treason and are suspects of misery. The vast majority of “investors” are phantom individuals who do not contribute to the local economy, despite being depicted by the government as just another trickle-down economics scheme. In fact, many of them do not even live in Cyprus. Some of them also have shell companies to launder money and own flats that remain empty. Those who sometimes do reside in Cyprus tend to live in gated communities, inscribing a growing cultural divide in the cities.

Cypriots seem unable to articulate their opposition to this scheme; either because of a pervasive and paralysing feeling of powerlessness (nothing really changes) or because the only source of truthful information comes when clashes of interest between elites in different countries, reveal parts of such reality to the public. Most media owners have pledged allegiance to the government, leaving little room for public debate or for providing a genuine voice for the concerns of the people. The relationship of the Anastasiades presidency to the local media is marked by a high level of dependency and control. By controlling most of mass media through a perplexed integration of journalists into the structures of government, information is tightly controlled. Many Cypriots have had their share of illusions on the narrative of a viable, long-term economic growth. According to the hegemonic narrative, everybody is benefiting, from the builder to the coffee maker and the small restaurant owner. But the truth is that most wealth can be traced to very few pockets.

ENVIRONMENTAL COSTS

The environmental cost of the development associated with the golden visa scheme is usually disregarded. The cost and time needed to conduct environmental studies would be a barrier to Cyprus becoming an investment destination. The Chairman of the Cyprus Property Owners Association had stated before the scandal and eventual re-conceptualizing of the program, that “demanding complete environmental studies from five-story buildings, thus increasing the workload of the Environmental Department and creating further delays, will only increase costs for the developers. A cost which will be reflected in the end price of the property, pushing prices up and creating a chain reaction in the market”. The developers have carte blanche on how high they can build and where they want to build without considering how this will impact the environment, the economy and the quality of life of citizens. Many of the new buildings block the views of old residential areas.

Architecturally, they are ruining the visual character of cities such as Limassol. The architecture of such buildings is intrusive, its size and shape reflecting the power and exploitative relations in which they are being brought into the picture, while its luxury kitsch aesthetic speaks a language to which the locals can only find empty in meaning. In Nicosia, the capital city, there are concerns over some of the buildings having no way of managing fire and evacuation procedures. The buildings are being placed in areas that may be detrimental to the water and the surrounding coastline geology.

The only area in Limassol that remains unaffected is the area around Lady’s Mile Beach, one of the most beautiful landscapes in Cyprus. The reason for this anomaly lies in the fact that the area is adjacent to the Akrotiri RAF military base where gigantic British radio listening communication antennas loom over the landscape. The military base is a vestige of British colonialism that remains active, often partaking in military operations in the Middle East.

GENTRIFICATION AND MARGINALISATION

The colonization of city space by new developments was viewed as a minor consequence of “development” at first, but has grown into a major problem, evident mostly for the city of Limassol but also in other major cities (Nicosia, Larnaca, Paphos). Some of the fading middle strata might still have the illusion of trickle-down profits, but the lower strata such as the working class have been displaced to the outskirts of the city, unable to find a voice.

Rents in Limassol and eventually to other cities have risen multiple times in the past few years to vertigo heights, excluding many Cypriots and other residents. Many young people end up residing with their parents even after they are married, without any comprehensive housing plan on the part of the government even after new and sharp increases in rents. Others live in nearby villages, or, if commuting is not an option, sharing flats. To combat the rising inequality, municipalities such as in Limassol have announced plans to construct low-cost housing. It is not clear, however, whether the plans will resolve the housing problem or whether they will accelerate the movement of old residents into parts of the city that are deemed as unmarketable to “investors”. Such housing schemes seem like an exoneration of the visa scheme.

As inequality rises, many middle and lower middle strata house- and flat-owners are willing to liquidate their assets by selling their properties to investors themselves. Others wait for the inevitable of vulture funds buying their non-performing loans. As property values near new malls, new buildings and the coastlines skyrocket, locals are forced out as rich investors move in. Cyprus is fast becoming a land to be sold at any price, recontextualizing the meaning of home. While it is not unusual to see Cypriots subscribing to the narrative of a viable, long-term economic growth, Cyprus, as well as being a country, has become a commodity in which land and identity are nothing more than commodities themselves.

If Cyprus is for sale, then what does home mean for Cypriots?

- Written by Leandros Savvides